Man Against Machine (Barbarian Poets 1/3)

- Ed Hinman

- Jul 28, 2024

- 8 min read

Updated: Aug 11, 2024

Facing the mechanized horrors of World War I, where men became expendable, some soldiers didn’t search for meaning, they created it through their art.

“The drift of modern history domesticates the fantastic and normalizes the unspeakable. And the catastrophe that begins it is the Great War.”

-- Paul Fussell, Historian

When Life Hangs by a Thread

In his memoir The Forgotten Solider, German infantryman Guy Sajer remembers this order inside a ruined city on the Eastern Front: “One-third of the men forward. Count off by three.”

He continues…

“One, two, three… One, two, three. Like a miracle from heaven, I drew a ‘one,’ and could stay in that splendid cement hole…

The fellow beside me had number three. He was looking at me with a long desperate face, but I kept my eyes turned front, so he wouldn’t notice my joy and relief…

The sergeant made his fast gesture, and the… soldier beside me sprang from his shelter with a hundred others.

Immediately, we heard the sound of Russian automatic weapons. Before vanishing to the bottom of my hole I saw the impact of the bullets… along the route of my recent companion, who would never again contemplate the implications of number three.”

Oh man, that is grim. Yet, Sajer’s experience typifies the foot soldier’s experience in war. Living or dying often depends more on luck than skill. Talk to anyone who has experienced serious combat, and they’ll tell you about their many close calls with death. Bullets that whizzed by, mortars that didn’t explode, and all the times they just missed drawing a “three.”

Though luck has always mattered in war, when machines entered the battlefield, luck began to matter even more.

Mechanized Warfare

At the dawn of the twentieth-century, European powers like Britain, Germany, and France were producing war machines like never before. Steel battleships and submarines patrolled the sea, while machine guns and howitzers ruled the land. By 1914 (the first year of The Great War), combat went from a colorful, romantic, and sometimes bloody escapade in the nineteenth century to a drab, mechanical, and nearly genocidal catastrophe in the twentieth. Instead of plumed hats and cavalry charges, modern soldiers wore steel helmets and manned killing machines like construction workers.

Once machines took hold of war, they would never let go. And like any machine that’s built to increase productivity, the war machines of the First World War increased the production of death at a speed and scale never before seen.

Howitzers blasted hundred-pound shells, bombs fell from the sky, flame throwers torched men in trenches, and machine guns spit out death at six hundred rounds per minute. During the four-plus years of that industrialized war, an average of seven thousand men were killed or wounded every day, most along the 20,000-mile jagged lines of trenches cut through the earth from Belgium to Switzerland – a narrow strip of death known as the Western Front.

Weapons and Mechanization unimaginable in the nineteenth-century.

At any given moment, bullets and shrapnel swarmed the battlefield like screeching locusts. One minute a soldier is sitting in his trench thinking about dinner, the next minute a shell mutilates him beyond recognition. There was no rhyme or reason for who died, most soldiers’ deaths were nothing more than ‘wrong place / wrong time.’

Consider the largest battle in British imperial history: The Battle of the Somme. Beginning in July 1916, it was a four-month slog fought by millions of men, most of whom had very bad luck.

The Somme

Following Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815, Europe experienced ninety-nine years of relative peace before the First World War. During that century, the British Army suffered approximately 50,000 combat casualties (excluding disease) from their imperial wars in Africa and Asia.

On the first day at the Somme, 60,000 British soldiers were killed or wounded. One Century: 50,000. One day: 60,000.

After 60,000 men fell that day, guess what British General Douglas Haig did? He ordered more men to charge into what was almost certain death from German machine gunners. And then more, and more, and more. As men as young as 16 huddled in their trenches before the attack, some were reported to mutter, “In five minutes I’ll be dead, in four minutes I’ll be dead…”

Going Over the Top on the Attack

After four months of General Haig’s meat grinder, the British Army gained six miles of dirt and lost 125,000 men, plus another 400,000 wounded. Counting German and French casualties, well over a million men were casualties during that four-month killing spree along a thirteen-mile front. Heaps of bodies lingered for days and even weeks in No Man’s Land. As survivors huddled in their trenches each night, they could hear their wounded crying for their mothers while sinking deeper and deeper into the mud until no sound could be heard at all.

The Somme was one of many battles from that war. Similar horrors occurred at the Marne, Ypres, Passchendaele, and Verdun (which I write about here). By the end of the war, after all the gas attacks, suicidal assaults, and unrelenting shells, an exhausted continent lost ten million men in battle – a generation gone.

They died because machines, created and operated by men, killed them wholesale. They died because dodging bullets and shells was a matter of inches, seconds, and above all, luck. They died, as Col. David Hackworth wrote about his own men killed in Vietnam, “because they zigged instead of zagged.” In modern war, there are a thousand variables outside of your control, yet it only takes one to send you to an early grave.

Search for Meaning

“The cruel fact that much of what happens – all of what happens? -- is inherently without meaning.”

- Paul Fussell, Historian

If you were lucky enough to survive the Somme, to what (or to whom) would you credit your survival? Sure, it could have been your buddy next to you, who yelled “Get down!” But what about all the other times you narrowly escaped death?

It’s unsettling to know how little control we sometimes have over whether we live or die. And because it’s unsettling, we look for ways to gain control of the uncontrollable. Prayer is a perfect example of regaining control. Through prayer, we acknowledge that a higher power is at work, that things aren’t random, and that everything (good and bad) happens for a reason. And because the deity has plans for each of us, we can rest easy knowing that whatever happens was truly meant to be. The result is less anxiety and more certainty. The result is (some) peace of mind.

This peace of mind was particularly important for the millions of soldiers along the Western Front who risked their lives every day. Unlike any war in history, the men who fought World War I were cannon fodder -- and that’s because of machines. By 1914, advances in mechanization had far exceeded advances in battlefield tactics. As a result, Generals on the offensive used close-order Napoleonic tactics, while those on defense used twentieth-century machines like the “machine” gun. The result was a blood bath. Thus, when you're just another pawn on the Western Front, believing in God’s cosmic plan goes from being a leap of faith to a practical choice -- a choice that protects your sanity.

Millions of soldiers fought and more than a billion shells were fired.

Divine Intervention

On multiple occasions during the First World War, British soldiers reported seeing angels above the battlefield. In 1914, "the Angels of Mons” were said to have streaked across the sky, covering a British retreat. Then there was “The Bowmen” near Flanders, where ghosts from Henry V’s army five hundred years before appeared on the battlefield and began “discharging arrows,” killing Germans “without leaving [any] visible wounds." Following that, were reports of “Angel Bowmen” slinging arrows from the sky.

According to Paul Fussell, it was "unpatriotic, almost treasonable" to doubt the Angels of Mons or Angel Bowmen.

Crucifixions were also reported. The writer Dalton Trumbo wrote, “Newspapers carried a story of two young Canadian soldiers who had been crucified by the Germans in full view of their comrades across No-Man’s-Land.” In another instance, a large wooden cross in the town cemetery at Ypres still stood after hundreds of thousands of shells exploded around it. When a shell did finally hit the cross, it didn’t explode, lodging itself in the cross until 1969. “In this acre of death,” one veteran remembered, “the high wooden crucifix still stands [as] an accidental symbol of the power of the cross.”

Besides angels, crosses, and crucifixions, soldiers sought control (and protection) from talismans as well. “No frontline soldier or officer,” historian Paul Fussell writes, “was without his amulet…, lucky coin, button, dried flower, hair cuttings, New Testaments, pebbles from home, [or] medals of Saint Christopher and Saint George.”

When you’re being pummeled by thousands of shells and rattled by millions of bullets every week, you’ll seek sanity anyway you can get it. By believing in the supernatural, talismans, and cosmic plans, soldiers could better manage the unmanageable.

Now put yourself in their muddy boots. What if, despite all the talk of divinity around you, your friends kept dying?

What if in the morning, your battalion had a thousand able men, and by the afternoon just fifty of you remained? Can you still accept this horror as God's plan? Can you still say with a straight face that “I’m alive for a reason” and “they’re dead for a reason?”

Men living on the edge of the world and their humanity.

Living through so much gloom and gore in the trenches, some men just couldn’t believe in the cosmic plan anymore. They stopped searching for meaning, and instead, decided to create it for themselves. These men were the Barbarian Poets of World War I.

The Barbarian Poets

“The artist’s job is not to succumb to despair, but to find an antidote for the emptiness of existence.”

- Woody Allen, Filmmaker

From the utter hopelessness of the First World War emerged a flurry of warrior poets and writers at a scale never seen before or since. Men born in the nineteenth century with Victorian sensibilities were hit by a twentieth-century sledgehammer at the Western Front -- a sledgehammer of industrialization that annihilated row upon row of uniformed young men; a sledgehammer of technology that threatened the inherent value of individual human beings. Ever defiant against the unfeeling machines and bureaucracies trying to kill them, these battle-hardened barbarians hoisted their pens and defended humanity with every bloody word.

British poets and writers like Edmund Blunden, Robert Graves, Siegfried Sassoon, and my favorite, Wilfred Owen, paradoxically elevated humanity by exposing the war’s inhumanity. Through their poems and prose, men were no longer “battalions or divisions,” they were individuals who suffered and mattered.

Edmund Blunden, Robert Graves, and Siegfried Sassoon -- British Infantry Officers and Barbarian Poets

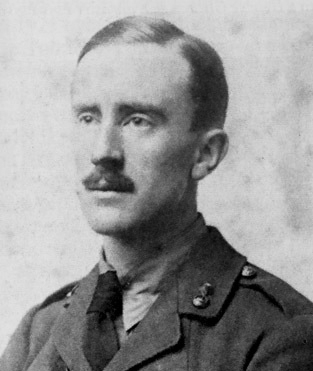

After the war, even more veterans emerged as writers. Earnest Hemingway, F. Scott Fitzgerald, John Dos Pasos, C.S. Lewis, and J.R.R. Tolkien -- all added to the Western canon, empowering human agency over the domination of machines.

In Parts 2 and 3 of the Barbarian Poets series, we’ll meet two of my favorites: the defiant poet, Wilfred Owen, and the king of fantasy, J.R.R. Tolkien. Though very different men (one an atheist, one a devout Catholic), they both suffered alike in the trenches, and they both – in their own unique ways -- reminded the modern world of this: We are not pawns, nor are we expendable or obsolete. We are flesh and blood, free and wild. We are not a means to an end, we are the end.

Till next time, Barbarians, find your wonder or create it.

Lieutenants Wilfred Owen and J.R.R. Tolkien

Comments